Tropical Plantations: Extraction and Regulating Laws

Gutta-percha first came to the attention of Europeans in 1656, when the English traveller John Tradescant brought samples back to London from Southeast Asia. It was attributed as the necessary requirement for the success of the undersea telegraph project. William T. Brannt quoted “It may be said without exaggeration that if Gutta-Percha and its properties had not been known, submarine telegraph lines would perhaps never have been successful.”

The trees to look for

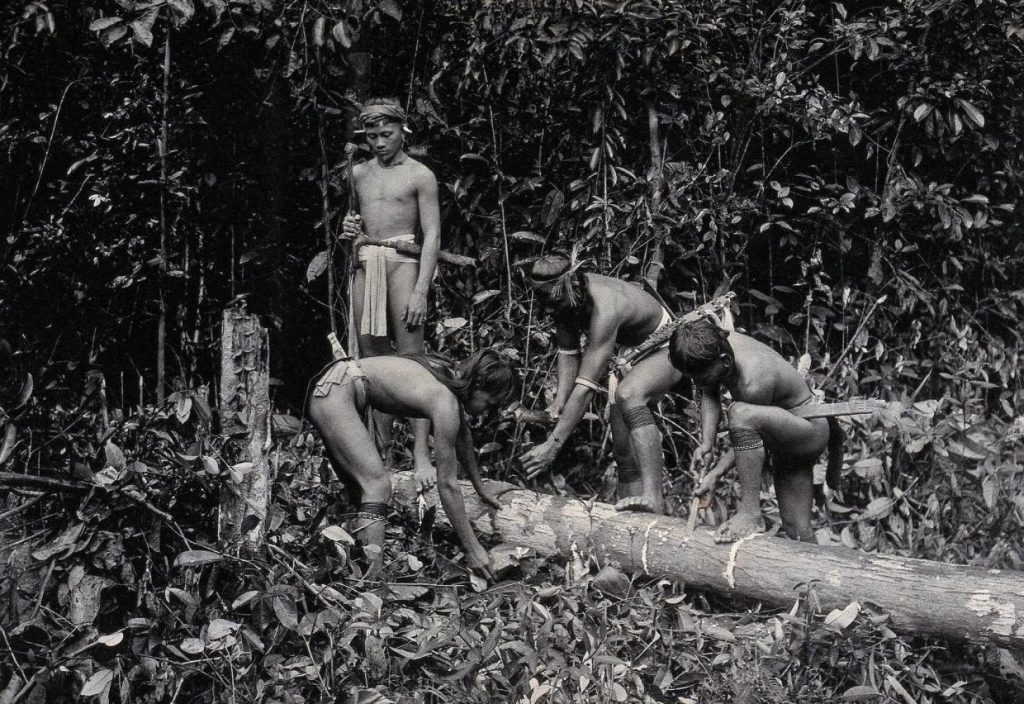

The question of what is the best method for collecting gutta-percha has troubled owners and dealers from the beginning. The trees found in the tropical forest regions of the Malay Archipelago, Borneo, and the Philippines, were inhabited by the remotest tribes. The trees were not easy to access, requiring both lengthy and difficult expeditions over rugged territory. The lack of easy overland or river transport routes made both collection and carriage of gutta-percha to market venues a difficult and time-consuming activity. The method of extractions of gutta-percha was basicin technique and had not changed before its use spread beyond Southeast Asia. Chinese, Dayak, or Malay woodsmen would enter the tropical forests however, there was quite often a hazardous and unpleasant journey and threats as wildlife would not flee human presence. At first, suitable patches were identified and then the woodsmen would build a wooden stage. It is well established that timber cutting is always perilous work, and there are increased chances of numerous deaths and injuries. After the tree is crashed to the forest floor, the branches are lopped off.

A General Account of the Extracting Method

Gutta Percha is found in narrow reservoirs running as black lines through the heartwood, and the woodsmen would make incisions into the trunk to drain. The Gutta Percha flows very slowly and coagulates quickly into a solid mass upon exposure to air. The warm, soft mass is then worked with cold water until a considerable amount of the liquid is mechanically enclosed. Following collection, the gutta percha would be cleaned several times and rubbed rolled into sheets, and folded into blocks; generally superior and inferior grades were mixed together. It was often further adulterated by unscrupulous Singapore merchants and arrived on the docks of the metropolitan countries in a filthy state where it needed considerable refinement.

Native Flora of tropical world

Gutta-percha can be derived from several tropical trees of the Sapotaceae genera Palaquium and Payena, especially Palaquium gutta. The trees are natural inhabitants of Southeast Asia. This plant is native to Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia, and Singapore. However, Gutta-percha is now believed to be increasingly rare and almost extinct in Indonesia. In Malaya, there are over 100 species of trees belonging to the Sapotaceae family, and all of them produce gutta-percha. In most cases, however, gutta-percha is mixed with various resinous substances and is therefore of too little value to be worth collecting. A few species, mainly the genera Palaquium and Payena, have gutta present in sufficient amounts to be of commercial importance. The best grade of gutta-percha is produced by Palaquium gutta, also known as Isonandra gutta or getah taban merah, in the Malay Peninsula.

The two vital defects of the method are, one, the method is very wasteful, the yield from each tree being a small proportion to the total amount. General thing from one-third to one-half of it is inaccessible to the process of ringing, and all the gutta percha within this portion is consequently lost; to this must be added the considerable quantity spilled on the ground through carelessness. The other defect is that it leaves the future unaccountable and unsustainable.

As soon as the Forestry Bureau was established in 1899, the felling of gutta-percha trees was prohibited. Rules and regulations were provided for tapping the bark of the tree in such a manner as to allow the latex to be secured without killing the tree. But these rules came in too late and much environmental damage was already done.

Labour, Capital and Trade

With some submarine telegraph cables requiring up to 180 kg of gutta-percha per nautical mile, the demand in terms both of labour and the number of trees was immense. This followed that local collectors in the forests of Southeast Asia were left to collect the product upon which global communications depended. The effort involved in finding the trees in the forests, and then collecting, carrying, trading, and shipping the product indicates not only a profitable trade but one that engaged much of the population. The trade depended upon the skills and knowledge of each indigenous group.

European Capital and Chinese Labour

Sir James Brooke’s strategy for the development was “European Capital and Chinese labour”. To bring order into the recruitment process, the government issued a resolution in 1899 legislating ‘Rules for the management and Regulations of Chinese Depots’. Some Chinese workers, both sponsored and unsponsored, came directly from China and were indentured on arrival in Sarawak. From 1905, other companies also began employing indentured workers from Java on their plantation estates. Indentured labour was ‘legally bound to the Company’s service and was liable to imprisonment for absconding,’ a benefit for the employer but considered a “mild type of slave labour”.Major developments and public opinion led to Chinese indentured immigration being abolished from June 1914 and the system of indentured labour being officially abolished by the British Government in 1917. For most, the phasing out of indentured labour created both a labour shortage as the Malay peninsula offered more attractive opportunities and instability in the labour force, as employees could ‘desert at any time to work for a neighbouring Employer offering higher wages’. Workers were further protected by the appointment of a Protector of Labour by the government in 1929.

Header image: Extraction of Gutta Percha from the Trunk in Sumatra (ref: London; William Trounce, 1898)

Author: Prabhat Rathva

Prabhat is an International Research Intern based in Mumbai, India. He is studying Engineering at IIT Bombay

Find Prabhat’s related work here: Gutta-Percha: Ecological Impacts and Unsustainability