Strategic Implementation of the Telegraph in India

Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major but ultimately unsuccessful, uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the form of a mutiny of Sepoys of the Company’s army in the garrison town of Meerut, 40 mi (64 km) northeast of Delhi (now Old Delhi). It then erupted into other mutinies and civilian rebellions chiefly in the upper Gangetic plain and central India, though incidents of revolt also occurred farther north and east.

The rebellion posed a considerable threat to British power in that region and was contained only with the rebels’ defeat in Gwalior on 20 June 1858. On 1 November 1858, the British granted amnesty to all rebels not involved in murder, though they did not declare the hostilities to have formally ended until 8 July 1859. The Indian rebellion was fed by resentments born of diverse perceptions, including invasive British-style social reforms, harsh land taxes, a summary treatment of some rich landowners and princes, as well as skepticism about the improvements, brought about by British rule.

Its name is contested, and it is variously described as the Sepoy Mutiny, the Indian Mutiny, the Great Rebellion, the Revolt of 1857, the Indian Insurrection, and the First War of Independence.

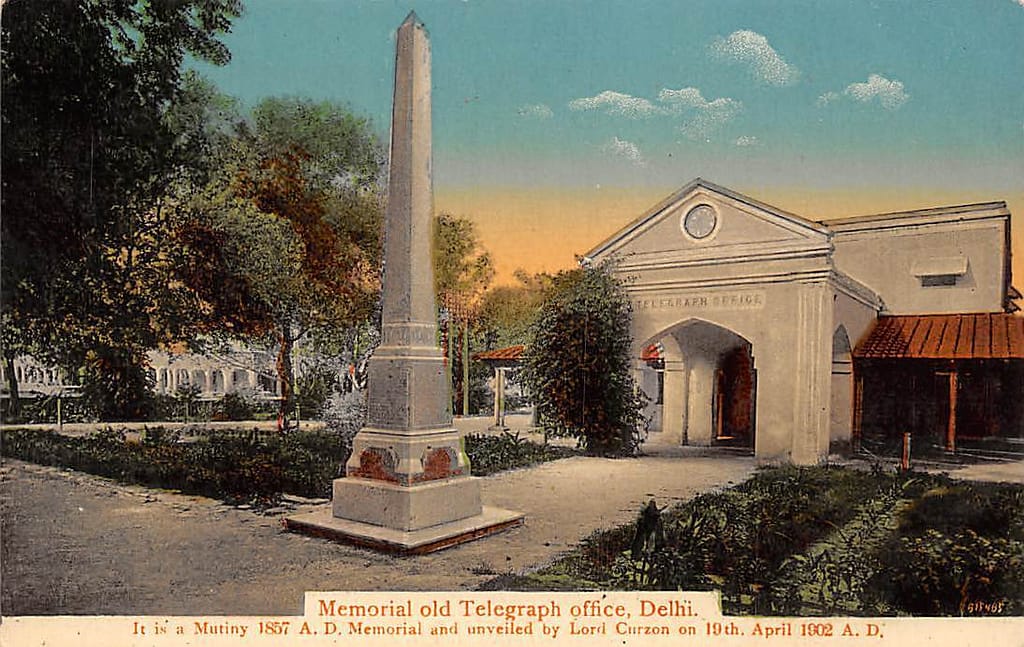

Indian Mutiny and Telegraph Memorial

The uprisings of 1857 were a major turning point in the history of British rule in India and an equally major test for the telegraph system recently built in India. 1857 was a communication crisis of enormous proportions for the British in India, and the telegraph has conventionally played a redemptive role in the huge volume of narratives generated around the uprisings.

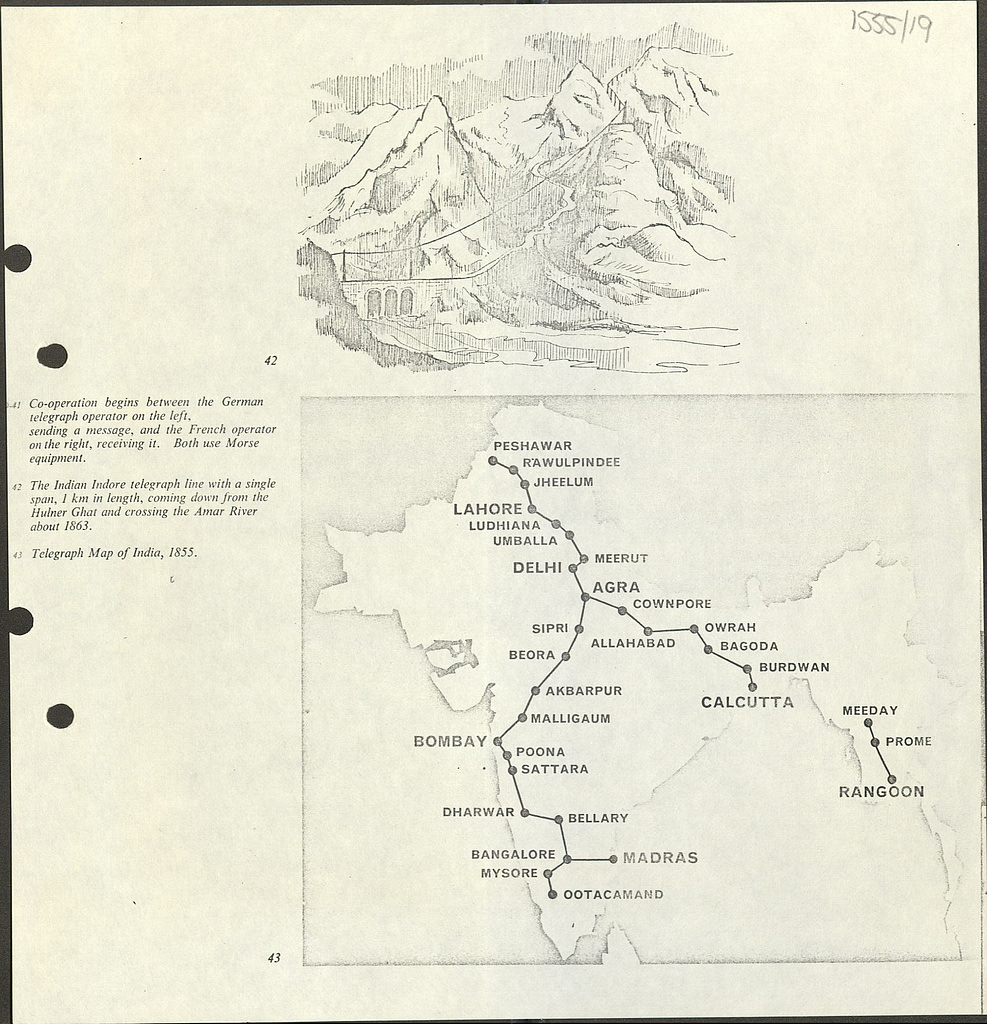

Lord Dalhousie paved the way for Imperial Telegraph Department in 1850. In 1854 the British in India completed an 800-mile telegraph line between Calcutta and Agra and this was further connected to Bombay and Madras. This system was the brainchild of a visionary inventor named Sir William O’Shaughnessy, and it did much to secure England’s control of India.

Sir Robert Montgomery, a British administrator in colonial India, had remarked after the mutiny of 1857, “The electric telegraph has saved India.” The comment is inscribed on a 20-foot obelisk at Mutiny Telegraph Memorial, Delhi as a souvenir to that event. The Telegraph Memorial made of gray granite was erected on April 19, 1902, “to commemorate the loyal and devoted services of Delhi telegraph office staff, on the eventful 11th May 1857,” so outlines the inscription on the obelisk. A decisive turn of events followed the dispatch from the telegraph office in Delhi which warned other British stations about the revolt.

Signalling amid Chaos

A brief account of the “incident of the Telegraph Office” was first published in 1902 titled ‘Delhi: Past and Present’. It gives credit to “irresponsible chatter of one clerk with another that warned Punjab of what happened at Delhi, and enabled the authorities there to take steps which at least scotched further mutiny and saved the position for the time being”

On the morning of May 11, 1857, the telegraph master, Charles Todd, who had left Delhi to check the lines which had been cut by the mutineers was murdered by them. However, his two assistants, William Brendish and J W Pilkington remained at the office till 2 pm, having received no message from the military which had been relying heavily on help from Meerut. Meanwhile, the signallers had been providing updates to the “Amballah” office of the events in Delhi. At three in the afternoon, Pilkington returned to the office with a military officer from the Flagstaff Tower where the telegraph officials had retreated to dispatch a “very meager official telegram to Amballah”. The last dispatch sent to Ambala said that the telegraph officer who had left from Delhi in the morning had been murdered. It ended with “we are off”. An 1862 guide to Delhi by Herbert Cooper says that the signaller at Delhi was cut down with his hand still upon the telegraph.

Expansion of Telegraph

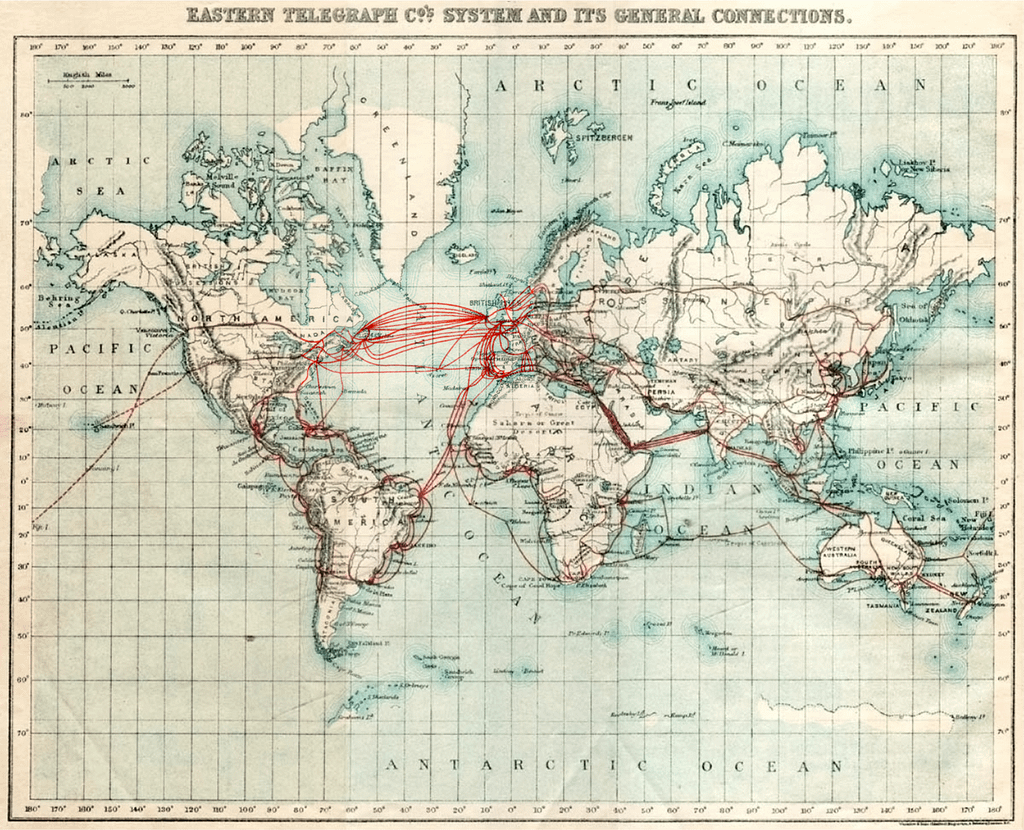

The impact of the telegraph message sent from Delhi has been highlighted in most British accounts of the period. Expansion of swift telegraph communication system to India was of strategic importance for the government after the Indian Mutiny of 1857; the urgent telegram requesting assistance had taken forty days to reach London. The telegraph went only as far as the coast of India and from there the message traveled by ship. The failure of the first cable was a significant blow. In the year of the Mutiny, British India boasted 4,555 miles of telegraph wire, and by 1859 the authorities endorsed plans to link the subcontinent with London. The British government believed the telegraph would provide the means for much greater central control of overseas possessions.

Similarly, after subsequent developments in Telegraph Industry – Malta was connected to Alexandria in 1868; France to Newfoundland in 1869; India, Hong Kong, China, and Japan by 1870; Australia to the outside world in 1871; and South America by 1874.

Author: Prabhat Rathva

Prabhat is an International Research Intern based in Mumbai, India. He is studying Engineering at IIT Bombay

Find Prabhat’s related work here: Tropical Plantations: Extraction and Regulating Laws