Recovering the Titanic’s Dead: the Mackay-Bennett

It is April, 1912. The air is cold, and the white glint of two icebergs can be seen on the rolling horizon. We are in the North Atlantic and the water is very cold. The sky is featureless grey and there is a light swell. There is a strong south-westerly wind and choppy sea makes spotting growlers more difficult. But as the compound steam engines slow down, the lookouts gaze out at the grey sea. All around the ship, there are deck-chairs, cabin fittings, broken and splintered pieces of wood. Something disastrous has happened here.

The cutters are swung out, ready to begin their gruesome task. They are looking for the dead.

Career of a Cable-Ship

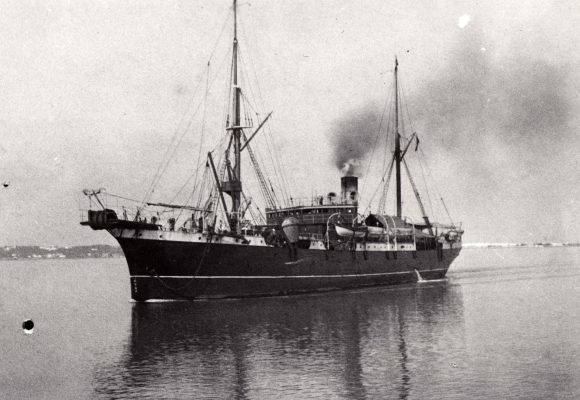

The Mackay-Bennett was in 1884 built by John Elder & Co. of Govan on behalf of the Commercial Cable Company. Two of the company directors were the New York Herald owner Gordon Bennett and the mining magnate John W. Mackay, and so the ship was named for both. (Random fact: a later ship, the John W. Mackay of 1922, was named for the latter, and appeared in Indiana Jones & the Last Crusade (1989).)

Built of iron, the Mackay-Bennett had a sheeting of greenheart wood. Based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, it was 270 feet in length and had a gross registered tonnage of about 1,700. Over the course of its career, it laid the Canadian shore-end of the fourth Transatlantic cable and diverted another Transatlantic shore-end from Canso in Nova Scotia to St-John’s in Newfoundland.

In 1922, after more than thirty years of service, the Mackay-Bennett found itself on the other side of the North Atlantic, reduced to being a cable storage hulk in Plymouth Sound. It would be another forty years before it was towed to Ghent to be scrapped. The ‘Coffin Ship’, as it became known, was a well-recognised landmark in the Cattewater, and was even sunk by German bombers in 1941 during the Second World War, only to be re-floated. But by the time of its scrapping, there were bushes growing out of its deck.

An unremarkable career, if a very long one for a ship. But history has a page for the Mackay-Bennett, and it involves a tragedy.

A Week to Remember

In 1912, whilst the Mackay-Bennett was in Halifax, the newest passenger liner of the White Star Line left Southampton on its maiden voyage. It was due into New York sometime around Wednesday 17th April. Five days into the voyage, on Sunday 14th April, at 11:40 pm (ship-time), the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic encountered an iceberg and was fatally damaged. It took two hours and 40 minutes for the Titanic to sink, and even though all its lifeboats were used and the lights of another ship could be seen, about 1,500 people died.

The news of the sinking was only a few hours old when the White Star Line chartered the Mackay-Bennett to recover the bodies. Its captain was Frederick Harold Lardner. The crew were given the option to remain in Halifax rather than undertake the task, although the company offered to double the wages of those who stayed aboard. To their credit, all the crew opted to remain aboard. In two days, the cable in the Mackay-Bennett’s cable-tanks had been taken out and replaced with ice, and so the cable-ship left its wharf at Upper Water Street, Halifax, with staff from John Snow & Co. (undertakers) and an Anglican canon aboard, as well as coffins, iron ballast, and canvas bags.

After a voyage full of fog and squalls, the Mackay-Bennett arrived at the reported final position of the Titanic. It was a gruesome sight that waited for the officers and crew. Although the Mackay-Bennett had called ahead to warn other ships to avoid the area, many corpses were mutilated and unidentifiable. There was also wreckage, and fragments of a grand staircase were spotted later by another cable-ship-cum-hearse, the Minia.

As each corpse was brought aboard, it was assigned a number, and any belongings were put in a bag with the same identifying number. Some of the bodies had jewellery in their pockets. Third-class passengers were found with their life savings.

The Mackay-Bennett retrieved 306 bodies – more than expected – and 116 of these were buried at sea (only 56 of the latter were identified). It received additional canvas bags from the Allan Line steamer Sardinian on Tuesday 23rd April, and on Friday 26th April met the older, larger cable-ship Minia – which had been chartered by the White Star Line for the same grisly duties – before departing for Halifax. It arrived in the morning of Tuesday 30th April at North Coaling Jetty No. 4, His Majesty’s Dockyard, Halifax, and unloaded its cargo. Church bells tolled for the dead. Amongst the bodies recovered were those of Mr Isidor Straus (owner of Macy’s Department Store), John Jacob Astor (the business magnate), and an unidentified child. This child was buried at Fairview Lawn Cemetery with a brass plaque courtesy of the crew of the Mackay-Bennett. On the plaque was the phrase ‘Our babe’. The body was eventually identified in 2007 through DNA testing as 19-month old Sidney Leslie Goodwin, son of third-class passengers the Goodwin family – none of whom survived the tragedy.

Rumours After the Titanic

In the years that followed, the Mackay-Bennett gained a reputation for bad luck as a direct result of having recovered so many of the Titanic’s dead. The author of The Mackay-Bennett: The Funeral Ship at the Titanic Disaster (2002), John G. Avery, reported the rumour of a ghost child heard and even seen by the crew, crying for its mother.

But perhaps the most intriguing story to emerge about the Mackay-Bennett comes in the form of a letter. In October 1978, the offices of the Cable & Wireless’ staff newspaper ‘Mercury’ on Theobalds Road, London, received a letter from a Mr Stray, a veteran of the cable-ship Transmitter. He wrote that during 1923, whilst off the coast of West Africa, he overheard the boatswain telling of his time aboard a cable-ship based in Halifax. In 1912, said the boatswain, this cable-ship had been sent out to pick up bodies from the Titanic disaster. After completing this grisly task, it was then sent out again, this time to use its grapnel to locate the Titanic’s wreck for the sake of ascertaining its exact position. The boatswain claimed they were successful in hooking on to the Titanic. They were in position for 24 hours but then had to abandon the grapnel and the rope.

This story, admits Mr Stray, may well have been a tall-tale, and as no expedition to the Titanic’s wreck has reported a wayward grapnel with a 3,700-metre long rope, we can suppose the boatswain was pulling someone’s leg. Also, we now know the Titanic’s reported positions (more than one was transmitted over the course of that night) were incorrect. If either the Mackay-Bennett or the Minia did successfully hook on to the Titanic, then this would have had to happen about 14 miles further east (where the wreck was discovered), and then the true position kept secret for decades afterwards. On the other hand, we can suppose (because it is fun) the wreck of the RMS Titanic was found by a cable-ship, and that cable-ship might have been the Mackay-Bennett.

Author

Duncan S. Mackenzie, RITTech, AMBCS

Digital Collections Officer, PK Porthcurno

Header image: the Titanic © PK Porthcurno Collection