Telegraph in Zimbabwe: A tool of imperialism

In Zimbabwe, communication techniques can be traced from pre-colonial communities. ‘Communication at a distance’ was an idea which has been present in one form or another since people had information worth communicating. Early attempts made use of smoke signals and drum beats, which local communities used to communicate. Traditional communication techniques were very useful as they enabled people to attend meetings, funerals or made people aware of an emergency. In some cases, they would send one person to deliver information to other communities at a distance where drum sound and smoke signals could not reach.

Smoke and drum used for communication in Mashonaland, Marandellas (now Marondera) under Chief Mangwende in pre-colonial times.

Smoke and drums were reliable traditional tools for communication in the pre-colonial era in Southern Africa. Smoke was situated at high level and in a fixed location, which enabled simple messages to be sent. Conveying a more complex range of meaning over long distances in a reasonable time was not to occur until the British attempted to establish long lines of communicating devices in the colonial lands. Around 1889, the British started to construct telegraph lines and stations as a strategy in their colonization process. The British South African Company (BSAC) introduced the telegraph, which allowed effective communication during the colonization process; as well as economic interests, the telegraph also served a military purpose.

First telegraph line

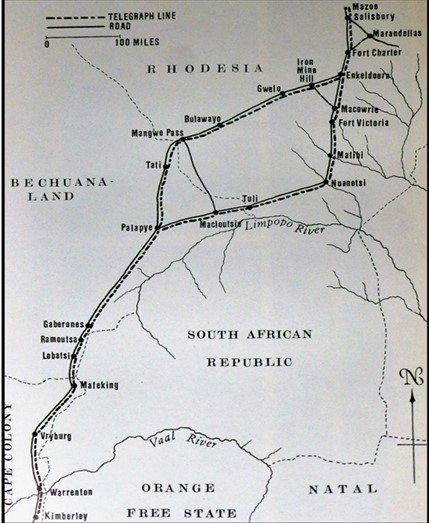

The telegraph line to Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) was started in 1890 from Mafeking to Palapye (three hundred and ninety kilometers) and completed by October 1890; Tuli telegraph office opened in 28 May 1891; Victoria by the end of the year; and Salisbury (Harare) was connected on 16 February 1892. Soon afterwards it was extended to Mazoe. The telegraph line followed approximately the route taken by the Pioneer Column. Telegraphists were stationed at each station: Fort Victoria (now Masvingo), Fort Charter (Chivhu), and Salisbury (Harare), and the Cape Colony transmitting offices were at Mafeking and Kimberley. Iron poles were used as far as Matibi’s kraal on the Lundi (now Runde) River, and then wooden poles carried the line, made of No 6 gauge iron wire, to Salisbury. However wooden poles, although cheaper and quicker to erect, were susceptible to elephant and buffalo damage and destruction from veldt fires and white ants.

In the early days, maintenance was carried out by the telegraphists themselves with their task often complicated by swollen rivers which were difficult and dangerous to cross. Construction of the line progressed at about five kilometers a day and was carried out by two hundred and fifty men, mostly supplied by Chief Khama. Once they entered Mashonaland however, they insisted on being armed; most carried old muskets that were generally loaded and at full cock, slung over their shoulders together with picks, spades and axes. This was to counterattack the resistance from the Shona people, who appeared to be more violently against colonial rule and its technology.

The telegraph line construction was a project of the BSAC (Cecil Rhodes the British Imperialist who was in charge for the colonization of Southern Africa) whose aim was to develop effective communication in colonial territories. This strategy ensured territorial occupation by the British, and was arguably decisive in their control over Zimbabwean land instead of the Portuguese.

Image: Courtesy of Zimbabwe National Archives – the Mazoe telegraph construction camp in 1895

The African Transcontinental Telegraph Company

Cecil Rhodes was keen to extend British South African or Rhodesian sub-imperialism and commercial power into East Africa. This led him to engineer the formation of the African Transcontinental Telegraph Company (ATTC) – of which he was Managing Director – in order to quench his imperial thirst.

The African Transcontinental Telegraph Company was formed to complete the communication connection between Africa (Colonial territory) and Britain. Clearly, this telegraph was a tool of imperialism since it was used mainly for the connection between extended British territories. It is also important to note that the gold fields and farming lands in Mashonaland allowed and encouraged the British to venture in to the Cape to Cairo telegraph scheme as part of their strategy to occupy African territory for economic gain. Telegraph lines were constructed alongside the railway for strategic reasons, as this ensured security in the movement of goods combined with effective communication.

African Resistance to Rhodesian Telegraphs 1892–1896

The BSAC was happy to exploit modern technology in order to occupy the African land. In 1891, some of Lobengula’s indunas (councilors) in Bulawayo suspected some dark and ulterior designbehind the extension of the telegraph from the south, and blurted out their suspicions by declaring that the British were bringing wire to tie up their king. They shook their heads when the real and actual purpose of the telegraph was explained, accepting it as truthful but declaring that the wire is a bad sign.

Lobengula appears to have prohibited his people from stealing copper wire from the telegraph by announcing to Ndebele people when the telegraph line was being erected no person would be able to pass underneath it without being killed. But King Lobengula was ineffective in neighbouring Mashonaland, where Shona people not only were disappointed to find that the perceived British magic had no effect upon their enemies but also saw the copper wire as too tempting not to be refashioned into ornaments.

The pretext for the BSAC declaring the Anglo-Ndebele War of 1893–1894 was the theft of copper wire by Shona people on the Nuanetsi River on the Mashonaland-Matabeleland frontier. The telegraph wires were frequently stolen by the locals to make bangles and snares for trapping game. Chief Gomala (Bere) resisted European occupation by repeatedly cutting telegraph wires between present-day Masvingo and Bulawayo. The European settlers responded by fining Chief Gomala (Bere) for the offence. Chief Gomala was requested to hand over cattle which he said were his, but had been left in his safe-keeping by King Lobengula. Chief Gomala then sent word to Lobengula saying that the British had stolen the cattle. This in turn started a chain of events that contributed to the onset of the 1893 Anglo-Ndebele war. When Lobengula sent soldiers to punish the Shona in question, the BSAC treated this as an invasion of their territory. The Matabele were subjected to a two-pronged attack by BSAC forces from Mashonaland and imperial forces from Bechuanaland.

Telegraphs played an essential role in the BSAC’s suppression of the Matabeleland and Mashonaland risings of 1896–1897. Most importantly, Bulawayo’s telegraph life line to Kimberley and Cape Town via Tati was never cut. Why not? The contemporary colonial explanation was that the Matabele (Ndebele) were terribly afraid of the telegraph wire, and hesitated to go near it, much more attempt to cut it. Telegraphic communication technology was much resisted in Mashonaland and the Chiefs were strongly against the Imperial government.

References

Neil Parsons (The ‘Victorian Internet’ Reaches Halfway to Cairo: Cape Tanganyika Telegraphs 1873-1926.

Zimbabwe National Archives: www.archives.gov.zw

Rhodesian Telegraphs – www.zimfieldguide.com

Header image Unknown artist from Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa – “tapping the line” and sending a telegram to London from near Fort Victoria on October 1891.

Author: Ian Tawanda Mugowa

Ian is studying Archaeology, Museum and Heritage Studies at Great Zimbabwe University. For the PK150 project Ian was partnered with Libby Gervais, a recent graduate of English at Exeter University. They have both researched the impact of the telegraph in Zimbabwe and have investigated the sensitive material in the Porthcurno archive.