British Science Week 2021

The Science of the Electric Telegraph

People have known about electricity for a long time. In 600 BCE a Greek philosopher called Thales noticed that if he rubbed a material called amber with silk, it would attract feathers and other light objects. You might have seen the same effect yourself, by rubbing a balloon or a plastic ruler on your sleeve.

People in ancient times also knew about magnetism, and used lodestones as compasses to help them navigate. They didn’t know how any of this worked though.

In 1600 CE, William Gilbert, who was Queen Elizabeth I’s doctor did two important things. He invented the English word electricity, which is based on the Ancient Greek name for amber, which was elektra. He also described the Earth’s magnetic field in detail.

200 monks prove that electricity flows

In 1746, a French clergyman and scientists called Jean-Antoine Nollet showed that electricity could flow. He gathered 200 monks into a human chain and got them to hold metal rods between each other. When he got the monk at one end to touch his store of electricity, the monks all reacted at the same time, showing that electricity flowed very fast.

Scientists now started to get very interested in what a flow of electricity, which we now call electric current, could do. Luigi Galvani found that electricity could make the legs of a dead frog twitch. Alessandro Volta invented the Voltaic Pile, which was the first simple battery. Humphry Davy, who was born in Penzance, found he could use electricity from a Voltaic Pile to make chemical reactions happen. This electrolysis led to the discovery of several chemical elements.

Using electricity to make a signal

The discovery which led directly to the Telegraph was made in 1820 by Hans Christian Oersted, who was Danish. He found that when you pass an electric current through a wire it makes a magnetic field which can move a compass needle. Not only that, but if the current goes in the opposite direction, the needle moves the opposite way. Now you could use electricity to make a signal.

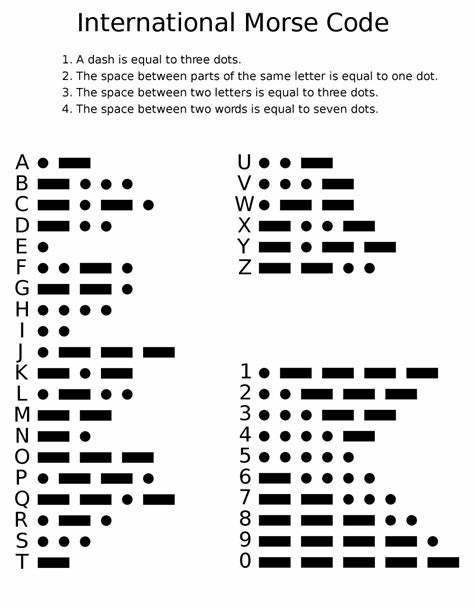

People tried different ways to make the electrical signals work to send more complicated messages. The one that worked best was Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail’s code made of dots and dashes, which was first seen in 1837. We call this code Morse Code. It is very versatile, and can use lights, sounds or simply a needle moving one way or another.

Rapid development of the telegraph system over 50 years

Development of telegraph systems expanded very rapidly. From simple electrical circuits connecting railway stations (so they could tell each other a train was on the way), within 50 years there was a network of electrical cables over the land and under the sea. People could send messages within a few minutes that used to take weeks or even months to be sent by letter.

After the telephone was invented and people could talk to each other through these cables, the Telegraph and Morse Code got used less and less. But today we have another way of communicating instantly which has even overtaken the telephone. The Internet is very fast, but the ideas behind it are the same as the Electric Telegraph from 150 years ago.

| Telegraph | Internet |

| Signals send through cables over land and under sea | Signals send through cables over land and under sea, and sometimes through microwave (radio) and satellites |

| A code with two symbols (dots and dashes) | A code with two symbols (0s and 1s) |

| Electric current flowing through wires in cables | Light passing through optical fibres in cables |

Can you tap out your own name in Morse Code?

Can you build an electric circuit to send your Morse Code with a lamp or a buzzer?

Can you find out what other changes were happening around the world from 1830 – 1900, while the Telegraph was being developed?

Paul Tyreman, Learning Facilitator, PK Porthcurno

Check out the British Science Week website for activity packs and further information!